Local Linear Trend models for time series

Simple time-varying regression

The bedrock idea of modern statistics is exchangability. An exchangeable sequence of random variables is a sequence $X_1, X_2, X_3, \ldots$ whose joint probability distribution does not change when the positions in the sequence in which finitely many of them appear are altered. Informally, this means that you could permute the sequence and this would not change the inferences about it.

Not all problems have this nice feature. The most common non-exchangeable problem is the inference of parameters in a time series. Time series analysis is a fundamental technique in data science that helps us understand and predict patterns in sequential data that evolves over time. Here, if you permute the sequence you lose all the information about what point came in which order-the essential feature of a time series.

Among the various approaches to time series modeling, Local Linear Trend (LLT) models stand out for their simplicity and effectiveness. These models are particularly useful when you need to:

- Track gradual changes in the underlying trend of your data

- apture both the level and rate of change at each time point

- Make short to medium-term forecasts while accounting for uncertainty

LLT models achieve this by decomposing a time series into two key components:

- A level component that represents the current value of the series.

- A trend component that captures the rate of change.

You can think of am LLT as a time varying regression slope, the level component moves up (and down!) the $y$-axis as time progresses, whilst the trend component rotates around the level. This approach is particularly valuable in scenarios where the trend isn’t fixed but evolves over time - think of retail sales during a period of economic growth, or user adoption of a new technology.

In this post, we’ll walk through implementing LLT models in Python using Stan. We’ll use the classic air passengers dataset as our example, which exhibits both trend and seasonal patterns, making it perfect for demonstrating the model’s capabilities.

The LLT model can be expressed by the following equations:

\[v_t \sim N(v_{t-1}, \sigma_v^2)\] \[x_t \sim N(x_{t-1} + v_{t-1}, \sigma_x^2)\] \[y_t \sim N(x_t, \sigma_y^2)\]Where:

- $v_t$ represents the trend velocity (rate of change) at time t.

- $x_t$ is the underlying state (level) of the system

- $y_t$ is the observed value

- $\sigma_v^2$ is the trend disturbance variance

- $\sigma_x^2$ is the level disturbance variance

- $\sigma_y^2$ is the observation error variance

Local Linear Trend models are one of the simplest time series models. Here we code them up in python using stan.

We will model this in pystan, using the air passengers dataset.

import pystan

import arviz as az

import matplotlib.dates as mdates

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import pymc as pm

RANDOM_SEED = 8927

rng = np.random.default_rng(RANDOM_SEED)

az.style.use("arviz-darkgrid")

%config InlineBackend.figure_format = 'retina'

try:

df = pd.read_csv("../data/AirPassengers.csv", parse_dates=["Month"])

except FileNotFoundError:

df = pd.read_csv(pm.get_data("AirPassengers.csv"), parse_dates=["Month"])

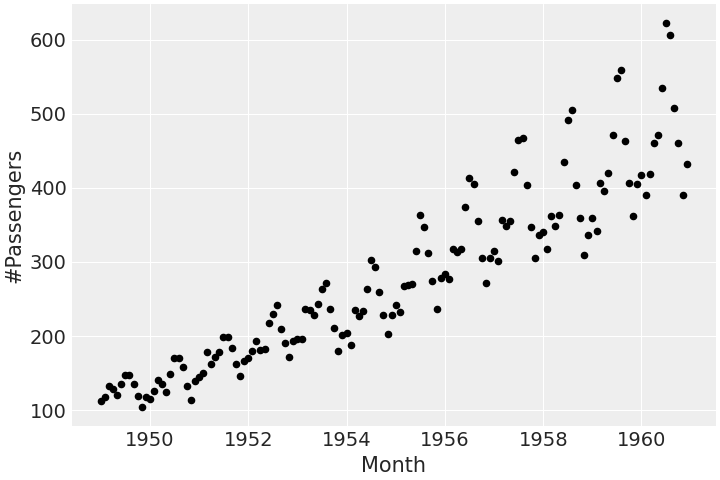

df.plot.scatter(x="Month", y="#Passengers", color="k")

This dataset tracks the monthly totals of a US airline passengers from 1949 to 1960. The time series displays a rising trend with multiplicative seasonality.

In stan we can write out model as follows:

stan_code = """data {

int N;

vector[N] X;

}

parameters {

vector[N] u;

vector[N] v;

real<lower=0> s_u;

real<lower=0> s_v;

real<lower=0> s_x;

}

model {

v[2:N] ~ normal(v[1:N-1], s_v);

u[2:N] ~ normal(u[1:N-1] + v[1:N-1], s_u);

X ~ normal(u, s_x);

}"""

Stan programs are organized into blocks that serve different purposes in the statistical modeling process. The main blocks are:

-

Data. This block declares the data that your model expects. Variables declared here are treated as known/fixed, and with a fixed type (e.g. int, float, array etc).

-

Parameters. Declares the parameters that Stan will estimate, which are the unknowns in your model. Parameters cannot use integer types, they must be continuous. Constraints here are enforced during sampling, and good constraints can improve sampling efficiency.

-

Transformed Parameters. Declares and defines variables that depend on parameters. Useful for derived quantities that are used multiple times. Transformed parameters are computed once per iteration and can access both the data and parameter blocks (and are declared after them).

-

Model. Contains the actual statistical model. Uses sampling notation with the ~ symbol.

-

Generated Quantities. Computed after sampling. Used for: predictions, derived quantities, model checking statistics.

Let’s break this down section by section:

Data Block:

data {

int N; // Number of observations

array[N] real X; // Input data vector

}

As input the the data the model expects is:

- $N$ is an integer representing the number of time points in our series

- $X$ is a vector of length $N$ containing our actual observations (like passenger counts)

parameters {

array[N] real u; // State/level vector

array[N] real v; // Velocity/trend vector

real<lower=0> s_u; // State noise standard deviation

real<lower=0> s_v; // Velocity noise standard deviation

real<lower=0> s_x; // Observation noise standard deviation

}

This section defines the parameters we want Stan to estimate:

- $u$ represents the underlying state (level) of the system at each time point

- $v$ represents the velocity (trend) at each time point

- The $s_$ parameters are standard deviations for different types of noise, constrained to be positive with <lower=0>

model {

for (t in 2:N) {

v[t] ~ normal(v[t-1], s_v);

u[t] ~ normal(u[t-1] + v[t-1], s_u);

}

X ~ normal(u, s_x);

}

This is where the actual model is defined through three key relationships:

v[2:N] ~ normal(v[1:N-1], s_v)

The velocity at each time point follows a random walk. Each velocity value is normally distributed around the previous velocity. $s_v$ controls how much the velocity can change between time points.

u[2:N] ~ normal(u[1:N-1] + v[1:N-1], s_u);

The state at each time point depends on the previous state (u[1:N-1]) plus the previous velocity (v[1:N-1]). $s_u$ controls how much random variation is allowed in this relationship.

X ~ normal(u, s_x);

Our observations $X$ are normally distributed around the true state $u$ with $s_x$ representing measurement noise or short-term fluctuations.

What makes this a “Local Linear Trend” model:

- It’s “local” because the trend can change over time

- It’s “linear” because between any two adjacent time points, we model the change as linear (through the velocity term).

- It’s a “trend” model because it explicitly models the rate of change (velocity).

We can run this model in Stan with the following code:

data_feed = {

'X': df['#Passengers'].values.astype(float), # Ensure data is float

'N': df.shape[0]

}

sm = pystan.StanModel(model_code=stan_code)

fit = sm.sampling(data=data_feed, iter=1000)

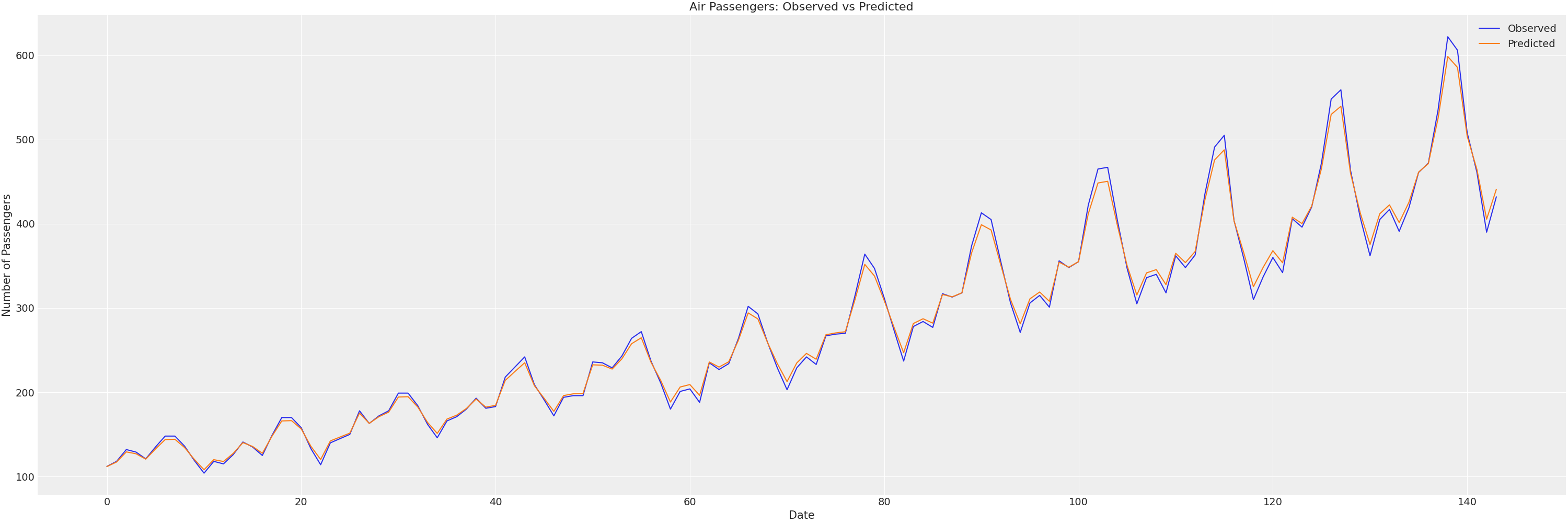

We can visually check the fit and the parameters with:

u_columns = [col for col in parameters.columns if col.startswith('u.')]

u_mean = parameters[u_columns].mean().values

df['pred'] = u_mean

plt.figure(figsize=(30, 10))

plt.plot(df.index, df['#Passengers'], label='Observed')

plt.plot(df.index, df['pred'], label='Predicted')

plt.title('Air Passengers: Observed vs Predicted')

plt.xlabel('Date')

plt.ylabel('Number of Passengers')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

We can measure our in sample fit with the following quantities:

fitted_values = u_mean

mse = np.mean((df['#Passengers'] - fitted_values)**2)

rmse = np.sqrt(mse)

mae = np.mean(np.abs(df['#Passengers'] - fitted_values))

mape = np.mean(np.abs((df['#Passengers'] - fitted_values) / df['#Passengers'])) * 100

r2 = 1 - (np.sum((df['#Passengers'] - fitted_values)**2) /

np.sum((df['#Passengers'] - df['#Passengers'].mean())**2))

print(f'MSE: {mse:.2f}')

print(f'RMSE: {rmse:.2f}')

print(f'MAE: {mae:.2f}')

print(f'MAPE: {mape:.2f}%')

print(f'R²: {r2:.4f}')

I get:

- MSE: 121.76

- RMSE: 11.03

- MAE: 8.12

- MAPE: 2.79%

- R²: 0.9915

Which indicates a pretty good fit:

- Average error around 11 passengers (RMSE)

- Only 2.79% average percentage error (MAPE)

The low MAPE and high R² suggest the model captures both the trend and seasonal patterns. The RMSE of 11 passengers is quite small given the scale of passenger numbers in the dataset.

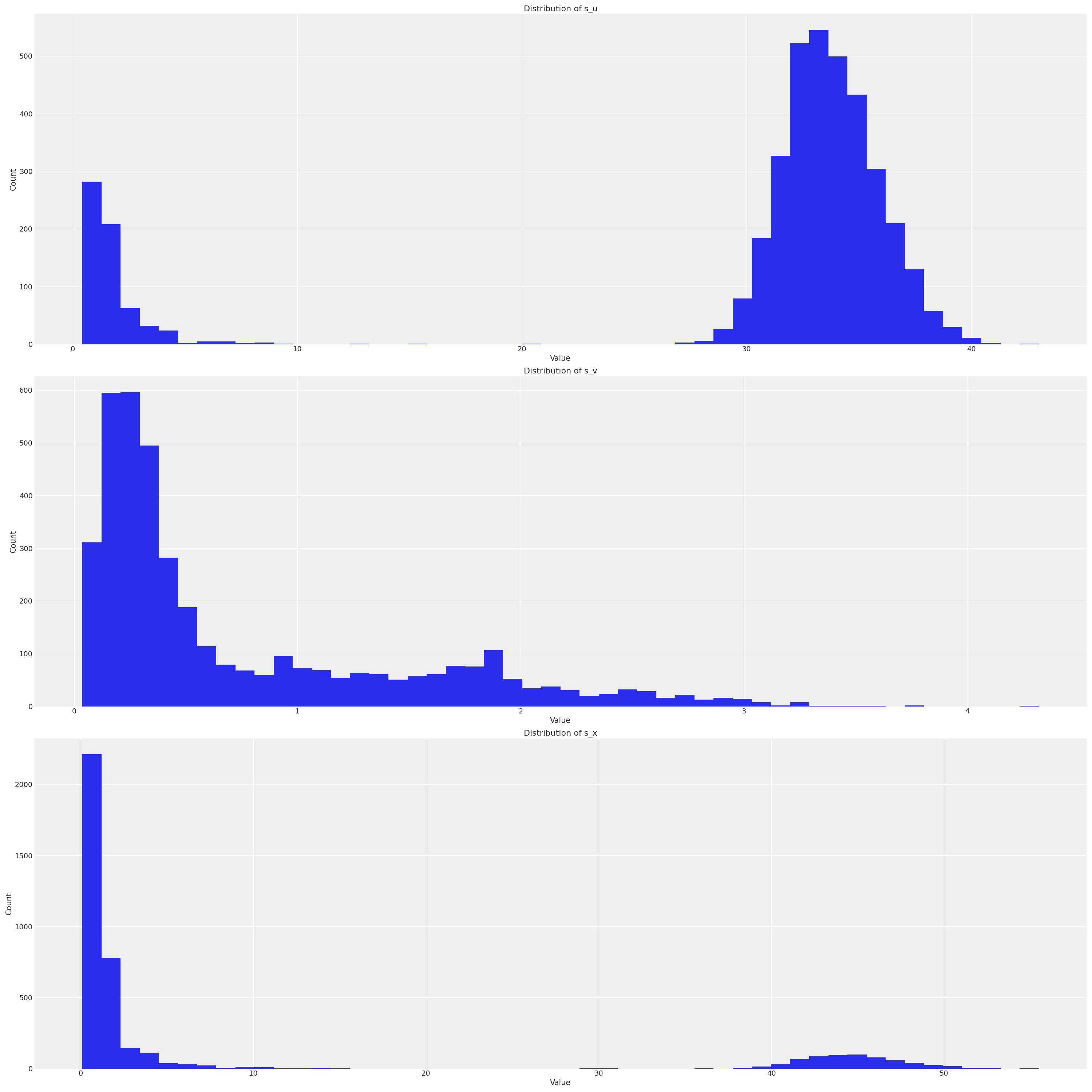

We can also plot the distribution of the fitted parameters:

params_to_plot = ['s_u', 's_v', 's_x']

fig, axes = plt.subplots(len(params_to_plot), 1, figsize=(30, 10*len(params_to_plot)))

for i, param in enumerate(params_to_plot):

# Get values for this parameter

param_values = parameters[param]

# Plot histogram

axes[i].hist(param_values, bins=50)

axes[i].set_title(f'Distribution of {param}')

axes[i].set_xlabel('Value')

axes[i].set_ylabel('Count')

axes[i].grid(True)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

To predict future points, we have to include the extra points in the original stan code:

stan_code = """data {

int<lower=0> N;

int pred_num;

array[N] real X;

}

parameters {

array[N] real u;

array[N] real v;

real<lower=0> s_u;

real<lower=0> s_v;

real<lower=0> s_x;

}

model {

s_u ~ cauchy(0, 2.5); // Half-cauchy prior

s_v ~ cauchy(0, 2.5); // Half-cauchy prior

s_x ~ cauchy(0, 2.5); // Half-cauchy prior

for (t in 2:N) {

v[t] ~ normal(v[t-1], s_v);

u[t] ~ normal(u[t-1] + v[t-1], s_u);

}

X ~ normal(u, s_x);

}

generated quantities {

array[N + pred_num] real u_pred;

array[pred_num] real x_pred;

// Copy the u values to u_pred

for (n in 1:N) {

u_pred[n] = u[n];

}

// Generate predictions

for (i in 1:pred_num) {

u_pred[N+i] = normal_rng(u_pred[N+i-1], s_u);

x_pred[i] = normal_rng(u_pred[N+i], s_x);

}

}

"""

Here the Generated Quantities block predicts future states based on previous states (python normal_rng(u_pred[N+i-1], s_u)), then generates observations from those states (python normal_rng(u_pred[N+i], s_x)).

We can run the model with this code:

data_feed = {

'X': df['#Passengers'].values.astype(float), # Ensure data is float

'N': df.shape[0],

'pred_num': 12

}

posterior = stan.build(stan_code, data=data_feed, random_seed=RANDOM_SEED)

fit = posterior.sample(num_chains=4, num_samples=1000)

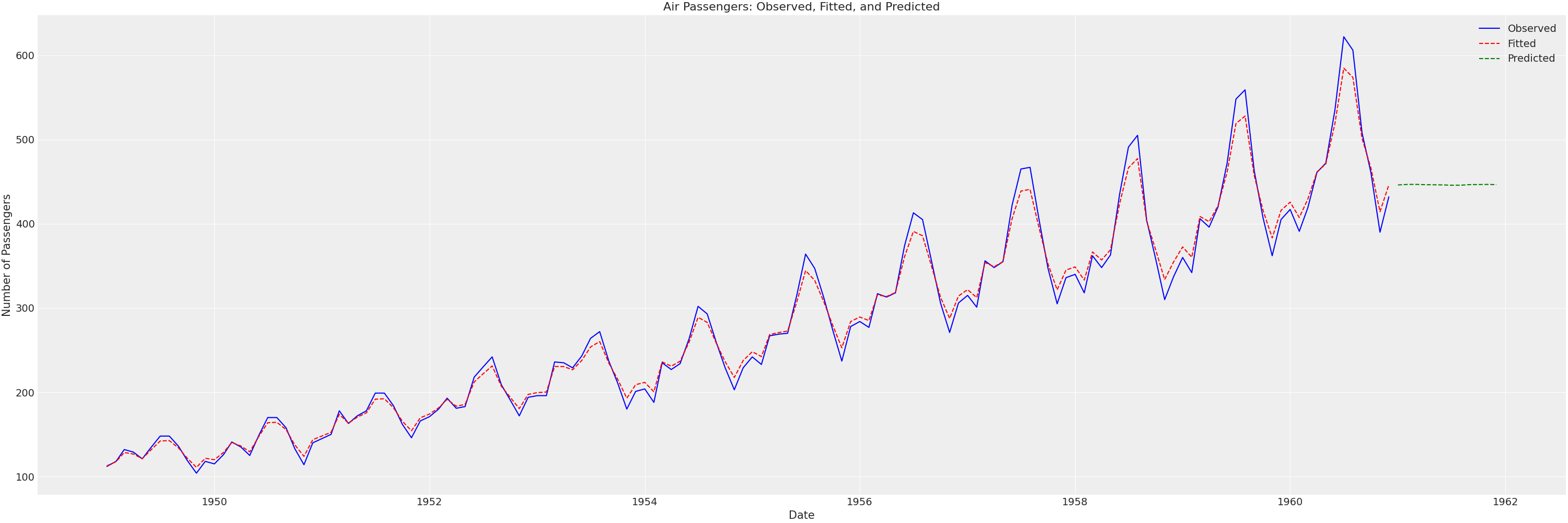

And then plot the fit and the predictions like so:

parameters = fit.to_frame()

u_columns = [col for col in parameters.columns if col.startswith('u.')]

u_pred_columns = [col for col in parameters.columns if col.startswith('u_pred.')]

u_mean = parameters[u_columns].mean().values

u_pred_mean = parameters[u_pred_columns].mean().values

pred_num = 12

last_date = df['Month'].iloc[-1]

future_months = pd.date_range(start=last_date, periods=pred_num + 1, freq='MS')[1:]

extended_df = df.copy()

future_df = pd.DataFrame({'Month': future_months})

extended_df = pd.concat([extended_df, future_df])

extended_df['fitted'] = np.concatenate([u_mean, np.repeat(np.nan, pred_num)])

extended_df['predicted'] = np.concatenate([np.repeat(np.nan, len(df)), u_pred_mean[-pred_num:]])

plt.figure(figsize=(30, 10))

plt.plot(extended_df['Month'], extended_df['#Passengers'], label='Observed', color='blue')

plt.plot(extended_df['Month'], extended_df['fitted'], label='Fitted', color='red', linestyle='--')

plt.plot(extended_df['Month'], extended_df['predicted'], label='Predicted', color='green', linestyle='--')

plt.title('Air Passengers: Observed, Fitted, and Predicted')

plt.xlabel('Date')

plt.ylabel('Number of Passengers')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

plt.show()

So, even though our model has a good in-sample fit, the out of sample predictions are very poor! We’ll have to do something about that!